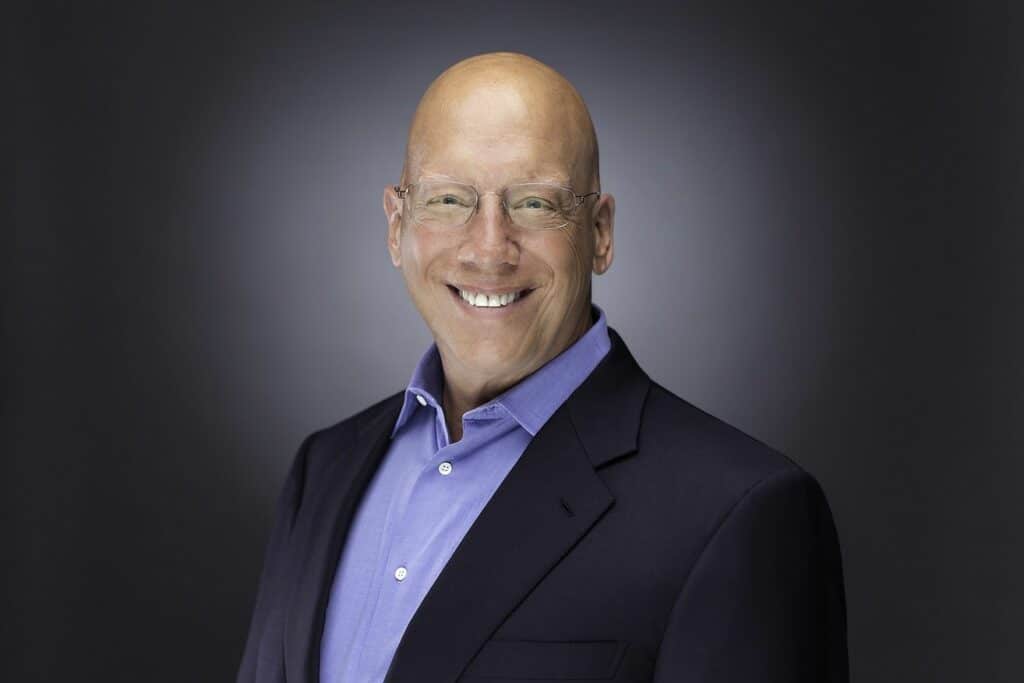

VITAC Chief Marketing Officer John Capobianco recently was featured on a national podcast regarding captions and accessibility.

The “Bars and Tone” podcast, a production through the Association for Higher Education Communications Technology Advancement (AHECTA), devoted its July podcast to the captioning sector, including discussion on live, pre-recorded, municipal, and web captioning services. The podcast makes the point that captions benefit everyone, with host BJ Attarian saying that captions shouldn’t be thought of as a burdensome mandate but, rather, “something that we want to do.”

Click here to listen to the podcast. Capobianco’s interview begins around the 33:15 mark. You can also read the transcript of the interview here below:

>> … Today, we are talking about captioning, and I’m joined by a very special guest, the chief marketing officer of VITAC, John Capobianco. He is joining us today over the phone. It’s a big company, the biggest captioning company, accessibility company in the country. You’ll see some of their captions if you’re watching the recent Stanley Cup finals, “America’s Got Talent,” “Tonight Show with Jimmy Fallon,” all the things that they caption. They also do conferences, graduations, events, and sports, which will be a little bit more relevant to our listeners here in the education field. John, what else can you tell us about VITAC and what a kind of average day is like? How much stuff are you captioning every single day?

>> [ Chuckles ] Well, sometimes it kind of amazes people, just the volume of captioning we do on a daily basis. We do about 550,000 hours of captioning a year. That’s a little bit more than a minute’s worth of captioning for every second of every day, 24/7/365.

>> Wow.

>> So, 2 billion seconds of captioning on an annual basis — just kind of an amazing thought when you think about that it’s people that do this. There are people that are listening to whatever the event or the broadcast is, and they are transcribing that into the written word and transmitting that to — it could be an event center, it could be a classroom, it could be the NBC News. And that gets put into the screen. Now, most people think of captions on real-time, on the morning news and stuff like that. You can see it. Or for a sporting event if you’re in a restaurant or another establishment where it might be kind of noisy, and they’re kind enough to put the captions on so you can actually know what’s going on when you can’t hear it. So, the average day here is a lot of realtime, what we call realtime, which is the live broadcast, and we’re captioning those. And, again, that’s true whether it’s a lecture hall or it’s an event center, and there’s some baseball game going on, for instance, or it’s a major event with a major corporation, and the keynote speech is being transmitted in text, as well as through sound. So, a lot of people think about that, but there’s also a lot of what we call “offline,” and you might think of as prerecorded programs. So, those files are sent to us, as well. And you mentioned some of those in the open. A lot of the TV shows and those kinds of things are prerecorded programs, so they come, and then they go to what’s called “offline.” That’s what we call it, anyway. And they actually make a transcript of what’s being said. They then take all that, and they time and place that verbiage. You’ll notice the difference when you see captioning. If there’s a lag between what somebody says and the words that are popping up, that’s because it’s being done real-time. It’s got to move from the person who’s speaking to the captioner’s ears. It has to be transcribed. It has to be sent back. And typically in that environment, it’s going through a bunch of technology, like encoders and those kind of things, that cause a little bit of delay. If you see the words coming up, and typically they come up at the time that somebody is speaking, that’s a prerecorded program. And if it’s really done properly, it’s timed and placed. That is, the words are placed near the people that are speaking. If it’s done properly, which we take great pride in, they make sure that the captions don’t cover anything important on the screen. By the way, those are also FCC standards. And we also include things that can be heard but are not necessarily the speakers. So, there’s some description of what’s going on, you know, “dog barks,” “clap,” “music playing.” You’ll also see, if it’s being done live captioning, you’ll see the words to songs that are being sung and lyrics and those kinds of things. That’s also a requirement. So, there’s a lot of stuff that’s going on. We also do up to 50 different languages in our Multilanguage services. We also do multicasting, where we are putting together the same transmission in both English and Spanish simultaneously. We do that, as well. And, by the way, that’s done in real time and in the offline. There’s a lot of activity with hundreds and hundreds of people online right now transcribing some audio that’s going on and turning it into the written word, which benefits lots and lots and lots of people.

>> That’s really amazing. And under ideal conditions, what are your live captioners — like, what’s their lag time from when they hear it to where they actually type it, minus all the encoders, just from their ear to the type?

>> Well, for the actual lag that’s introduced by the captioner is about a second or two. That’s really all it is. The rest of that time is all technology delays. Encoders and those kinds of things cause additional delays.

>> Right.

>> But the captioner themselves is basically — this is what’s really strange, too, and people don’t think about this because — and I’m very familiar with that because I’ve only been in this business for about a year and a half and before that I thought the TV did the captioning, just like everybody else. [ Laughs ] A normal typist can type at about — a fast typist does what, 40 to 60 words a minute? Most people talk in normal, casual conversation at about 180 words a minute. The average broadcaster is at about 225 and usually ramps up to about 280 and sometimes higher than that, 280 words a minute. These captioners keep up with that level. Our normal captioners think about a couple of hundred words a minute, 200 words a minute, as normal speaking, and that’s how fast they translate this information from the spoken word to the written word. They do that in our company. We mandate a minimum of 98% accuracy, and most of our people are well above that. And that’s just their normal daily work, and this is what they do all day, every day. And they enjoy it. I was amazed a year and a half ago, when I came to the company, and I went out and met many, many, you know, hundreds of captioners because most of them work remotely, and they mostly work from home. It’s something that’s a lifestyle business for them that they enjoy. And beyond the fact that they enjoy their work, they feel great pride in their delivery of service to the community because there are 50 million deaf and hard-of-hearing people in the United States alone, and they rely on the captions to be able to not only be included in society — we call that accessibility — but also, more importantly, for disaster preparedness and emergency situations, it’s the only way they can get information because, of course, they can’t hear it. You can add to that there’s 83 million millennials. 58 million of them watch videos without sound, according to the projections that we’ve seen on places like Facebook, where 85% of all videos watch without sound on. That means there’s another 58 million millennials that are receiving information typically on their mobile handheld through videos, and if your video is not captioned, it’s meaningless, because they can’t see anything coming out of it. And what’s worse than that is if you let the machines caption it, and then you’re the recipient of the stupid remarks that the machines make [Laughs] since they are generally in the 70% correct stand, facility. Anyway, that’s kind of when we see the ASR engines. Most of them don’t work all that well. They’re fine for some things. You know, Siri works, but how often does it get a word wrong? And the problem is, unless captions are at least 98% accurate, they don’t work for people who can’t hear. They could be funny, but they’re not — by the way, the deaf and hard of hearing don’t think that’s funny at all.

>> Mm-hmm.

>> But having it be highly accurate is not only part of the law, but it’s the right thing to do.

>> Right, and we talked about, or you just talked about something I was going to hit on there. You’re taking all your captioning in with human captioning.

>> Correct.

>> And we have this huge AI and computer-generated, really, insurgence of captioning. But it’s still not there yet, especially for things that are critical, like health and safety information, tornado warnings, weather information. That — you just really can’t get to that level anywhere close, right? You have to use the humans still.

>> It’s just not accurate enough. Listen — I don’t throw any cold water on new technologies that are coming along. We use some ASR here, too, because we have voice writers, as well as stenocaptioners, so they use interpretive language. But there’s a person there, and if something goes wrong — the problem with the automated engines is nobody’s monitoring it. So, when it makes a mistake — because every word it does is a guess, right? That’s what it’s doing. It’s guessing. “I think it’s this.” If they get it wrong, there’s nobody there to correct it. The deaf and hard of hearing are used to this. Most people who aren’t that don’t know, but if you’re watching captions, and you see a dash followed by words, that means the word prior to the dash was an error. The dash means “I’m correcting the error,” and the correction is immediately following that. So, the fact that we have captioners associated with this means that even if it’s ASR working, we have humans actually overseeing what’s going on. When you try to use them without that, listen, they’re making great strides, and we’re all proud of the work that’s going on in ASR. But it can’t caption the way a human can. It doesn’t have the human intelligence behind it that the captioner does. So, typically, you see things like synchronous problems. The words are on screen for — they come too fast, or they come too slow. They catch up. The accuracy and completeness is way off. Usually, on things like proper nouns and foreign phrases, you can see a lot of times when people are using engines instead of humans. That works pretty well if you can feed it a script, like, if people are working off of scripted environments. And the problem is, as soon as they go off script, you wind up seeing a bunch of blanks on the screen because the ASR engine doesn’t know what they said. So, speaker accents can cause all kinds of problems with that. So, there’s a lot of the human element. When you think of captions, you got to think of them as a combination of art and science. The science part can be dealt with, but the human part is really important because the recipient is a human, and what they’re looking for is the human context and the punctuation and all the things that the machines still have problems with. Maybe someday they’ll get to the right spot. I don’t think that’s going to be in my lifetime, but they continue to make that better every day. We believe in human captioning because our job is not just the captions. It’s the quality and service that we provide to the industry, not just the words themselves.

>> Absolutely, and that’s a big thing here in the education field is making sure that this huge accessibility push that’s been going on more and more recently, especially as a lot of things have moved over to digital and technology, just making sure on campus that everybody’s included and everybody is able to get the information. Can you tell us a little bit where we can expand this in the education field?

>> Well, when we think about education, we got to think about more than just the accessibility for the deaf and hard of hearing, even though that’s the primary mission that we have. We also need to think about English as a second language. We need to think about the benefit of transcriptions that can be available when you do captioning for sessions, whether they’re training sessions, seminars, lectures, or whatever they are. Think about the fact that if you do realtime captioning for a lecture, let’s say, not only do you make sure that words are presented for those who are not necessarily English as a first language, but English as a second language, but everybody has availability of the transcript of that spoken session. That’s of great appeal, I believe, to the educational community because it’s effectively notes that everybody can use to better understand what happened. By the way, that’s not contained only in the education world, even though that’s what we’re talking about. Corporations find the same things. We see a huge increase in corporations doing training sessions and keynote speeches and their seminars and their big meetings, all captioning those things. Again, not only because they’re presenting the information in another view — that is, not just auditory but in the written word — but they also have the benefit of the transcripts that come from all of that, which I think is greatly important for the education community.

>> Absolutely. And we’re almost out of time here with you today, but can you give us some information of how to get in contact with you, if someone’s interested in reaching out?

>> Well, I think the best way to contact us and find out more about is just to go straight to our website. We take a lot of pride in what we put out there. It’s vitac.com, and you can find out all about us. You can contact us. You can get a hold of us there and see all the different things we do and all the different kind of programs that we offer in the marketplace. And, by the way, just to make sure everybody knows this, getting captions on your files is “A,” easy, “B,” it’s quick, and “C,” it’s not all that expensive, when you think about the quality and the value you get out of it. So, just want to make sure that everybody knows that, and again just come see us at vitac.com. We’d love to help you out.

>> Thank you so much for your time, John. It was a very interesting interview, and I think it’s going to be a huge benefit to our listeners. Thank you for joining us on this edition of “Bars and Tones.”

>> Great. Thank you very much.

>> John Capobianco, thanks for joining us here today. Now, Hal, we’ve heard a lot of things here today, but when it gets right down to it, captioning, it shouldn’t be something that is “Oh, my gosh, I have to go caption this stuff.” It should be something that we want to do.

>> Right. So, Mark Chen said something really important, which is that captioning is something that benefits all of us. We often think of captioning for Section 508 compliance for accessibility and also because of broadcast guidelines. But, really, when we’re watching a video in a noisy environment, and we turn captioning on, then suddenly we’re able to follow the video along. My dad, for instance, was hard of hearing. He was functionally deaf. He could follow conversation, but for him captioning was a godsend. In fact, he sought out theaters that actually provided captioning equipment, which actually some do. So, he could go to a movie theater and actually follow along with the movie along with everyone else. So, when we think of captioning, we often think of captioning for a special case, but the reality is captioning is something that impacts all of us. So, it’s really something that you want to do for your own work, but, also, you want to be an advocate for other people, as well.

>> And, you know, it’s becoming easier and easier to do it. Heck, even with just dropping the files onto Vimeo or YouTube, Final Cut now, you can caption right inside the NLE. So, it’s really becoming easier. It’s becoming much more commodity for colleges, universities, really, everybody to be able to do.

>> Yes, actually, you know, one of the things that you probably would follow from this conversation we’ve had today is that there are standards in place for doing captioning that are easy to follow, and now you’ve got multiple paths in terms of being able to get your captioning. You can do captioning yourself for short-form content. Certainly there are tools now that — like MovieCaptioner and tools like that — that allow you to do it. But if that is a burdensome effort for you, there are, as you have heard, commercial services that can handle captioning for you and in most cases fairly reasonable. The price on captioning in general has come down a whole lot. And, again, the technology is there now. One thing that we always have to keep in mind, though, is machine translation is still not quite there yet. And so, while it can be useful for things such as key-word searching and stuff like that, we’re not at a point where machine translation is good for 100% accuracy. It’s still just not quite there.

>> Our thanks to John Capobianco. He is the chief marketing officer at VITAC, vitac.com.

Click here for a full transcript of this edition of “Bars and Tone.”

The goal of AHECTA is to promote and develop the use of campus communication, cable, and video services as instructional, informational, and entertainment tools in higher education.